There is one memory that I do know what to do with: stick it up a dark, secret place and chew on it with muscles perforated by the tranquilizers I receive each day. A single incident, stuck, like a damaged elevator, in the utmost basement of my thoughts. I have tried to drag it into the light with me, to make it accompany me as I ascend the stairs. I was climbing a stairwell in a dark and grimy shaft. I did not realize I was trapped with an escaped convict until I glanced up at a TV monitor suspended from the corner. The building on the screen was the one that I was in. Police cars had surrounded us. My stairwell companion was to be executed on live TV as soon as he took the first step outside. This plan was announced by a pale, mournful newscaster who wore a black patch across her left eye.

I did not have time to dwell on the possible nature of her tragedy. Between her somber words, I heard labored breaths a few stories below. At that time I could still think clearly. I stood rooted to the spot, absorbing a vivid description of how the man beneath me was to be decapitated. Already a crowd had gathered in the parking lot of this structure to witness the event first-hand. When I heard this, I was not afraid of the man on the steps somewhere below. I was afraid of watching him lose his head on TV. This memory has found a place in me as dark and sticky as the stairwell itself. It cuts off here. The stairs are rammed into a wall, offering no way out - up or down. I stand on a cold cement step, inhaling the chemicals released by fear. I am terrified of being forced into the role of a voyeur. Or did I already say that? My bones are becoming soft. My knees buckle at the entrance of bewilderment. Has anyone caressed these feet, which now fail to take the necessary steps? Take a deep breath, my counselor says, whenever you stand and face the waves.

There was that day when Emile and I were lying in the grass behind a beheaded cathedral, admiring how the spire's torn edges scraped gothic scars into the sky. And when I rolled over on my stomach, he imitated the sihouette's flirtatious friction, by drawing a bitten fingernail across my back. Those were beautiful and lucid days. I remember those days well. But what leaves me in dark uncharted waters - what I cannot see for all the blinding white tiles - is why on the morning after being in the stairwell, I woke up and saw - the convict had been decapitated in my bed. And they asked me to clean up the mess. Can I help it that when I scrubbed the empty sheets I thought of unknown pleasures of the flesh? Can I blame it on the strings of white mucus, languidly descending from my pillow into the pool of blood on the floor? I know, I can't. I don't know what to say.

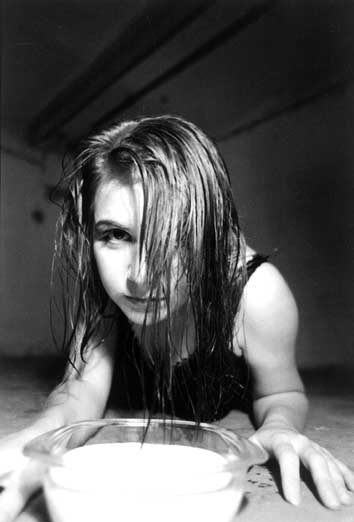

A bucket stands next to me, filled with dark, strange-smelling water. I smell it still before I put my lips to milk. I am scrubbing the sheets and pillows with a sponge. I see it still, when I smell the milk: the blood-soiled sheets, laced with translucent white strings. A policeman strolls through the room, watching me work. He walks in and out repeatedly. My stomach tightens into a fist-sized knot. I wondered what it was that I had done. Would it be clearer to anyone else? My thoughts are never as transparent as the residues found on used sheets. When I looked up from the scrubbing, I saw a woman outside my bedroom window, standing on top of a hill across from my house. She was watching me through binoculars.

I have asked so often who this woman was.

I have asked so often if it was me who watched.

Like mine, her hair was pulled back very tightly from her face.

Foto "Milk" (Claudia Reinhardt)